EDUCATION CHAPTER

The upper class in America and Europe used ivory extensively in accessories and household items. Most surprisingly, the greatest demand for ivory was for making billiard balls, which were found on the billiard table of almost every manor house. This led to intensive hunting for elephants and prompted a company in New York to offer US$10,000 reward for a replacement for ivory.

American inventor John Wesley Hyatt successfully developed a substitute for ivory using natural materials and patented it in 1870 as "celluloid." It became a prototype of future plastic.

Belgian-American chemist Leo Hendrik Baekeland created first fully synthetic plastic product called Bakelite. It is resistant to flame, heat and water, and has superior electrical insulation propertities. Bakelite sheets were commonly used in electrical appliances.

The term “plastic” appeared in dictionary.

German chemist Hermann Staudinger postulated that macromolecule, also known as polymer, are formed by monomers joined together by covalent bonds. The rapid development of modern plastics was driven by the swift application of this concept.

World War II broke out. The war created shortages of macromolecules, including natural rubber, and drove further study into synthetic materials. The development of synthetic macromolecule industry gained momentum.

Two British chemists discovered a way to turn petroleum byproduct, ethylene, to polyethylene, which was widely used in modern packaging. Petroleum byproducts soon replaced traditional materials like wood, wool or iron as raw materials in production because they were much cheaper. The widespread use of fossil fuel went hand in hand with popularisation of plastics.

From 1930 to 1945, synthetics like nylon, chloroprene rubber, styrene-butadiene rubber and polyethylene were developed in succession

World War II ended. The use of plastics transitioned from military to civilian applications, leading to a surge in low-priced plastic products.

Plastics industry thrived.

Professor Richard Thompson of the Plymouth University created the term “microplastics” in his paper.

The global production of plastics over this 20-year span exceeded half of the overall production of plastics since its invention.

The invention of plastic as a substitute for ivory saved not only the elephants but also valuable or rare natural resources such as wood and wool. It also made a wide range of consumer goods more affordable and improved the life of the working class. However, the plastics industry soon found a market for short-lived products (short-lived plastics) and promoted “Throwaway Living”. When durables were replaced with disposables, it marked the arrival of a new age - the Plastic Age.

Plastic bags were originally created to save forests. Paper bags were prevalent and resulted in a lot of trees to be felled. In 1959, the Swedish engineer Sten Gustaf Thulin invented Vest Bag (the most common plastic handle bags) which quickly took off because it was light, durable and afforadable.

Ironically, people use plastic bags against their intended purpose. In 2019, BBC interviewed Thulin’s son Raoul Thulin who stated that his father had intended for plastic bags to be reused multiple times to reduce reliance on paper bags and save trees. But the way people used plastic bags was a betrayal of his father’s intention, which the widespread use of "disposable" plastic bags has led to the pervasive spread of plastic waste.

According to the latest report by the EPD in Monitoring Solid Waste in Hong Kong, plastic waste accounted for about one-fifth of total MSW in 2023, with an average daily disposal of 2,120 tonnes. Among them, the most by ranking are plastic bags, plastic / polyfoam cutlery and plastic bottles in descending order.

In the area of recovery, there has been a gradual increase in quantity. About 128,000 tonnes of plastic waste were recovered in 2023, which is 100% more than the amount of 64,000 tonnes recovered in 2018. Nonetheless, this remains relatively small compared to the overall MSW recovery. The waste plastics recovery rate in 2023 was 14% of total plastics consumption, with over 86% of the plastics still going to the landfills.

From the invention of plastic in the 19th century to its industrialisation around 1950, the global production of plastics grew by leaps and bounds. The annual production of plastics was two million tonnes in 1950 and reached 438 million tonnes in 2017. At present, over half of the world’s plastics are produced in Asia.

From 1950 onwards, the cumulative global production has reached 9.2 billion tonnes with over half of it being produced after 2004. This indicates the production of plastics over the past two decades had exceeded the total of the previous 50 years.

Most of the plastics produced globally were used as packaging materials including product packaging, disposable food and beverage containers.

As reported by a study, the global recovery rate of plastic waste since 1950 was less than 10%. Among the rest, 14% were incinerated and 76% disposed of at landfills or stranded in nature.

When gargantuan proportions of plastics entered the environment, they caused serious ecological harm. Plastics comprised 80% of the marine litter and were estimated to be around 75 million to 199 million tonnes. Research projects that by 2050, there could be more plastics than fish in the ocean by weight. The adverse environmental impact of plastics demands urgent attention.

Exposure to ultraviolet light in the troposphere causes airborne microplastics to decompose and release greenhouse gases.

Earthworms are farmers’ helpers. They loosen the soil and their waste acts as organic fertiliser. Presence of plastics in soil stunts earthworm growth and affects crop yield.

Microplastics can clog the pore space in soil, consequently reducing soil permeability and damaging soil structure.

Plants can become covered or entangled in plastics, which disrupts photosynthesis and inhibits their growth.

When plastics undergo photodegradation, toxic additives in them leach into the sea.

Native organisms are carried by plastic debris to faraway places and became invasive species.

In the ocean, microbial colonisation on plastic surfaces drift with currents and spread diseases.

Plastics do not only cause physical damages to corals but also hamper their gas exchange and access to sunlight.

Plastics sink to the seabed and are ingested by marine benthos, whose predators then move the plastics up the food chain.

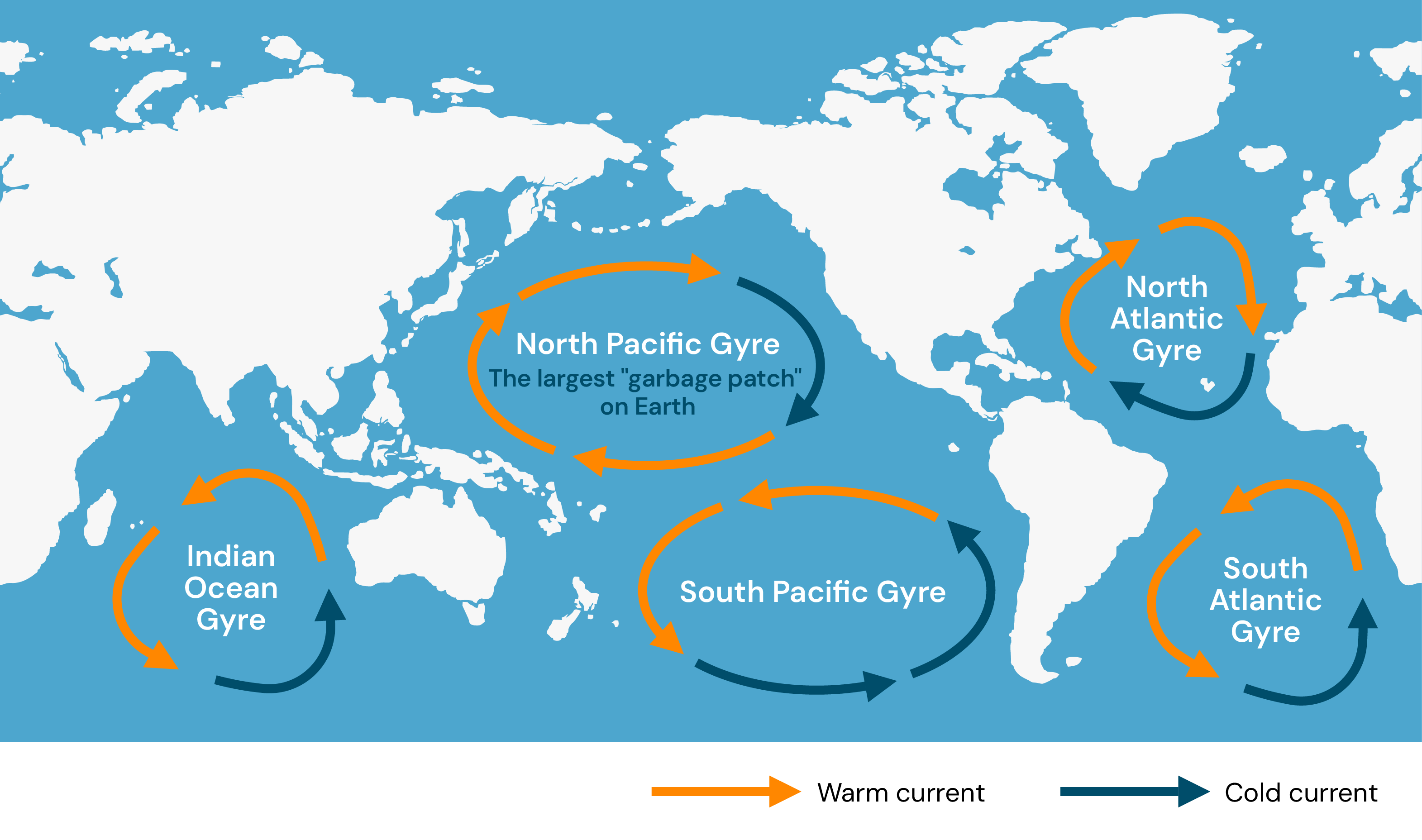

Waste plastics are very light and can be carried far by wind and ocean currents when they enter the sea. Ocean gyres create vortexes of densely-packed garbage patches.

The largest garbage patch is located in the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence zone, off the coasts between California and Hawaii. The North Pacific Garbage Patch covers 1.6 million square kilometres, an area equivalent to about 1,434 times the size of Hong Kong.

Five major ocean currents: North Pacific Gyre, South Pacific Gyre, North Atlantic Gyre, South Atlantic Gyre, Indian Ocean Gyre.

Microplastics are plastic fragments that are less than 5 millimetres in size. They are very tiny and come in different forms such as fragments, fibres, films and pellets.

They are deliberately made to a specific size. These microbeads or plastic pellets are manufactured to be added to products or used in production.

Microbeads are added in personal care products.

Plastic pellets as raw materials.

They are the fragmentation from plastics, which come from different sources such as fibres from synthetic textiles, particles produced by tyre abrasion, and degradation of plastic waste stranded in nature.

Plastic waste decomposes into microplastics.

Micro-fibres which came off from the washing of synthetic textiles are microplastics.

Microplastics are everywhere. They can be found in our everyday food:

*The data were collected from different studies so the range reflects variations in sample sources and study methods.

Airborne microplastics enter lungs when we breathe.

Microbeads added in cosmetic and care products are absorbed into human body through epidermal infiltration.

Some research reported that we ingested an average of 50,000 microplastic particles a year. According to a 2020 study, microplastic particles smaller than 2.5 µm can pass through intestinal absorption into the circulatory system. Microplastics also showed up in human stools, blood and various other organs as other studies revealed.

The Plastic Shopping Bag Charging Scheme (plastic bag levy) was launched. Supermarkets, convenience stores, medicare and cosmetic stores were required to charge a minimum of HK$0.5 for each bag provided.

A Green Lunch Charter was launched to encourage schools to stop using plastic or Styrofoam food containers and implement on-site meal portioning.

Plastic bag levy was extended to the whole retail sector.

Plastic-Free Takeaway, Use Reusable Tableware and Plastic-Free Beach, Tableware First campaigns were launched with about 700 restaurants participating to encourage the public to reduce using disposable plastic cutlery.

”Plastic-free” School Lunch Pilot Scheme and Pilot Programme on Installing Smart Water Dispensers in Schools were launched for installation of “Four Treasures” (refrigerators, steam cabinets, dishwashers and disinfection machines) at schools and encourage students to use or bring their own reusable food containers, cutlery and water bottles.

Reverse Vending Machine (RVM) Pilot Scheme was launched to encourage the public to recycle plastic bottles through the provision of an instant rebate (HK$0.1 per plastic bottle).

Public consultation on the Producer Responsibility Scheme (PRS) on Glass Beverage Containers began.

Plastic bag levy was enhanced and raised to HK$1 for each shopping bag provided.

The first phase regulation of disposable plastic tableware and other plastic products including Styrofoam tableware was enacted to ban provision of plastic straws and disposable tableware for dine-in and takeout orders, and sale of plastic-stemmed cotton buds, umbrella bags, glow sticks etc.

The PRS on Plastic Beverage Containers and Beverage Cartons will be introduced into the Legislative Council.

*Projected date

China started regulating plastics production and waste more than 20 years ago.

Urgent Notice on Immediate Ban on Production of Single-use Polyfoam Tableware.

Notice of the State Council Office on Restricting the Production, Sales and Use of Plastic Shopping Bags (known as the Restrictions on Plastics) .

Technical specifications for pollution control during collection and recycle of waste plastics.

Prohibition of Foreign Garbage Imports: The Reform Plan on Solid Waste Import Management.

Cosmetics and cleaning products containing microbeads and microbead additives were labelled as “high pollution” and “high environmental risks” products in the Comprehensive Catalogue for Environmental Protection (2017).

Gradual phase-out schedule for the production of household products containing microbeads was laid out with a complete ban on sales set for 2023.

Opinions on Enhanced Control Measures against Plastic Pollution.

Catalogue of Plastic Products Restricted and Prohibited from Production, Sales and Use (Draft for Comments).

Determination of Microbeads in Cosmetics.

The State Council tightened regulations of waste imports in 2017, followed by the implementation of an import ban on twenty-four types of solid waste in 2018. The measures gave rise to its nickname “Twenty-four Flavours”.

Prior to the import ban, China imported more than half of the world’s waste plastics of which many came from developed countries in Asia or the West. These countries would recover high-value recyclables that are easy to recycle, such as metals, locally and exported low-value waste like plastics, which required complex handling, to other countries. The import ban aimed to tackle the severe pollution caused by the massive influx of largely untreated plastic waste imports and trafficking.

In 2019, the Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics was published. The Containers and Packaging Recycling Act regarding raw materials for utensils, containers and packaging was amended:

In 2022, the Plastic Resource Circulation Act was implemented:

In 2022, the Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act was passed requiring all packaging in the state to be recyclable or compostable by 2032, cutting single-use plastic packaging by 25% and mandating the recycling rate of plastic packaging to be over 65%.

In 2019, the Directive on single-use plastics was passed:

Today, 60% of African countries (34 countries) have measures in place to restrict plastic use including a levy on or prohibition of plastic bags.

The notable countries are: